Chronic Pain & Human-Computer Interaction

Dr. Michael Poor pioneers research to enrich tech access for chronic pain sufferers.

In a 2011 TED talk, Dr. Michael Poor described his childhood Christmases the same way many of us would:

he’d wake up, run downstairs to confirm Santa’s midnight visit, and begin tearing into the red-and-green wrapped packages to see what treasures lie inside. But “growing up Poor,” as he calls it, though not in the monetary sense, meant that even on Christmas morning, an inherited curiosity of technology soon took over as toys were disassembled, analyzed, reassembled and eventually turned into spare parts for the family’s next robotics project.

“We played with them for about four or five minutes,” he said. “But then it was time to take Teddy Ruxpin, crack that bad boy open and see exactly what made him work.”

The assistant professor in Baylor’s School of Engineering & Computer Science doesn’t tinker with classic toys from the 1980s much anymore, but his passion for invention, combining technology and movement, is stronger than ever. Inspired by his father, a celebrated entrepreneur, renowned developer of animatronic figures and professor at Bowling Green State University’s college of business, the younger Poor specializes in human-computer interaction (HCI) and is using his talents in tech to transform quality of life for those suffering from pain and physical limitations caused by disease processes, chronic conditions and catastrophic events. After completing three combined degrees and multiple teaching appointments at Bowling Green and Tufts University, Poor joined Baylor’s faculty in 2012 and currently directs the University’s HCI Research Group.

After two decades immersed in a rapidly developing field like HCI, what’s interesting, he says, is that in that time—and even as far back as a decade before that—much of the physical, human-technology experience hasn’t changed.

“Many typical ways of interacting [with technology] haven’t changed in 30 years,” he said. “We are still manipulating data through the old, tried and true methods of mouse, keyboard and screen.”

Even touchscreen technology, which began adoption by the general public in the early 2000s, was utilized by professional HCI researchers since the early 1980s. Arguably what’s changed the most, he said, isn’t the way we physically access technology but how the ability do so has drastically separated physically challenged individuals from the rest of the population. And that’s a big problem.

“As we become a more digitized society, it becomes more difficult for some to gain access to information,” he said. “As people get older, there are physical limitations in how they can move, interact with and relay information to a computer.”

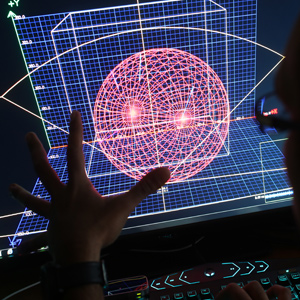

Poor’s work drills into the emerging study of gesture technology, where instead of relying on fine motor skills, users employ broader movements of the hand, arm and body in general to operate anything from a television remote, iPad or laptop to an automobile.

Having recently been awarded funding from the National Science Foundation’s Early-concept Grants for Exploratory Research (EAGER) program, he will spend the next two years designing the early stages of an interactive work space for people experiencing movement-limiting, chronic pain. With the help of two Baylor graduate students, Poor said his team plans to pursue multiple studies, producing various angles to attack the same problem. They will ultimately work toward a software solution with practical implementation for making the physical use of technology simple, natural and pain-free.

Besides his father, there’s another close family connection that motivates Poor’s work, and especially his current project, while increasing his understanding of its impact. His wife, Lauren, a lecturer in Baylor’s history department, struggles with symptoms of fibromyalgia exacerbated by long periods of sitting, writing and using a computer. Through her, he’s learned how chronic pain issues necessitate a completely adjusted routine in day-to-day life.

“The more you use a muscle, the higher the chance of it developing chronic pain,” he explained. “Today there are many professions creating this kind of problem. A person with chronic pain can’t even sit down in the living room to watch television in a normal way without an adaptive chair or body position. I’ve learned to appreciate the tiny interactions we go through every day and that most of us take for granted.”

Baylor, Poor said, offers not only outstanding professional and academic resources to support HCI breakthroughs like the ones he’s chasing but also a supportive atmosphere for doing work that matters. The University’s Computing for Compassion (C4C) initiative, he said, plays a major role in aligning his research with Baylor’s Christian mission. Through C4C, his project will have direct access to Waco-based organizations for older adults, which will connect Poor to exactly the kinds of people who he hopes one day will realize long-term benefits from the systems he’s incepting.

“What I find most rewarding is to know that one day, someone will have better access and better experiences interacting with a computer,” he said. “To see the effects of coming up with a solution that never existed before is why I do it.”